|

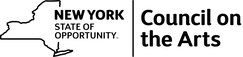

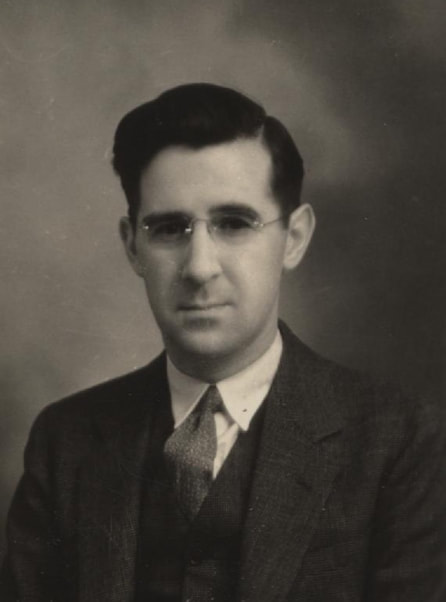

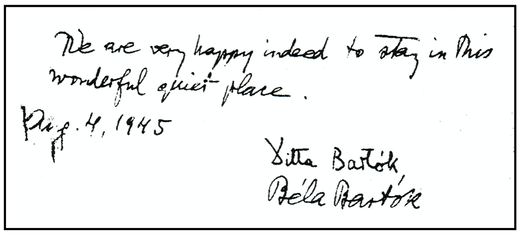

Dear Friends, As we follow the terrible current events in Eastern Europe, we learn a bit more each day about the history, the geography, and the people of Ukraine. Recently, a package arrived at the museum that brought the news closer to home. Inside were the personal effects of one of the greatest musical composers in human history. The box contained bow ties, a vest, glasses, and a pair of concert shoes stuffed with newspaper dating to 1942. These are the clothes Béla Bartók wore to performances in Europe back before WWII. Bartók came to Saranac Lake 80 years ago. He spent the last three summers of his life in the village, seeking respite from leukemia. Here, working in humble surroundings with little money and no piano, he found the tranquility to compose some of his greatest works, including the Concerto for Orchestra and the Third Piano Concerto. A tiny, eccentric, brilliant man, Bartók was not interested in fame or fortune. His music can feel inaccessible to people who aren’t trained musicians or familiar with folk songs of Eastern Europe. His story can seem as distant and as foreign as his music. But lifting his little shoes out of the box, it’s like he walked right into the present day. Back in the 1940s, Saranac Lakers didn’t pay the great composer much notice. Not only were international visitors commonplace during the tuberculosis years, but the events of WWII were grabbing all the headlines. As more and more young men went off to war, families followed the news overseas, charting the advance of troops on maps, learning the names of far away places they had never known before. The War felt intensely personal to Bartók. From here in Saranac Lake, he worried for the safety of his eldest son who had remained in Budapest. He feared for his second son, who was serving in the Pacific in the U.S. Navy. Having lived during WWI and the Russian Revolution, the composer was acutely aware of the horror of war and its tendency to transcend borders. Bartók’s personal history moved between many present-day European countries. He was born in 1881 in the town of Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary (now Romania). After his father’s sudden death, the family lived for a time in Nagyszőlős (present-day Vynohradiv, Ukraine) and then to Pozsony (present-day Bratislava, Slovakia). Young Béla studied piano in Budapest, and he developed his interest in folk music. He traveled the countryside, collecting and researching folk melodies of the Roma people.* He recorded songs in peasant villages with his wax cylinder Edison machine, notating Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian, Ukrainian, and Bulgarian folk music. He also collected melodies in Moldavia, Transylvania, Algeria, and Turkey. He incorporated elements of traditional songs into new compositions. Beloved in Hungary, Bartók performed throughout Europe. Perhaps wearing these same concert shoes, he performed in the Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv and Odessa in 1929 and 1936. Then came WWII. Hungary joined the Axis Powers. Béla’s anti-fascist views were well known, and his wife Ditta was Jewish. They fled the Nazis to New York City. Bartók left his life’s work in Budapest, including hundreds of recordings of ancient folk music. Miraculously, most of the cylinder recordings survived the war, as did his sheet music transcriptions of 13,000 songs. But Bartók died in New York City in the fall of 1945 thinking his recordings were destroyed. Millions of people, entire communities, and countless melodies had been erased by antisemitism, fascism, and war. The great composer who once walked the streets of Saranac Lake devoted his life to preserving diverse cultures of Eastern Europe. Now, the museum is honored to preserve his last few belongings. With this pair of shoes that fled the Holocaust, we remember Bartók, and we contemplate the incredible beauty and enormous tragedy of Ukraine and its neighbors. Be well, Amy Catania Executive Director *Roma people were once widely referred to in the English language as “Gypsies,” a term considered pejorative due to its past use as a racial slur. Sources: -Bartók, Peter, My Father, 2002. -Soroker, Yakov, Ukranian Musical Elements in Classical Music,1995. Images: -Béla Bartók's shoes. Historic Saranac Lake Collection, courtesy of the Estate of Peter Bartók. -Béla Bartók's ties and eye glasses. Historic Saranac Lake Collection, courtesy of the Estate of Peter Bartók. -Béla, Ditta, and Peter Bartók in Saranac Lake, 1944. Courtesy of My Father by Peter Bartók. -Bartok using a phonograph to record folk songs in Zobordarázs, Slovakia. Courtesy of My Father by Peter Bartók. -The Bartók Cabin. Illustration by James Hotaling. THE BARTÓK FUND

Historic Saranac Lake has established a fund to support the preservation and display of the Béla Bartók Collection, the maintenance of the Bartók cabin, and our work to interpret the story of Bartók in Saranac Lake. We welcome your support. Please donate to the Bartók Fund or contact us to find out more.

2 Comments

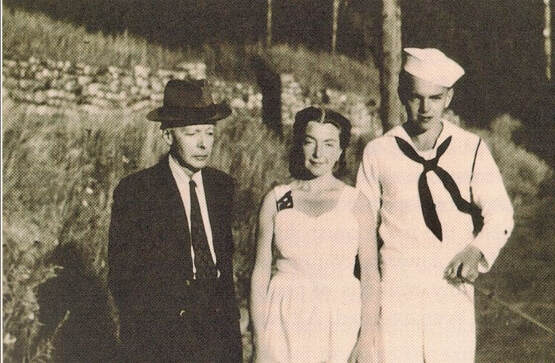

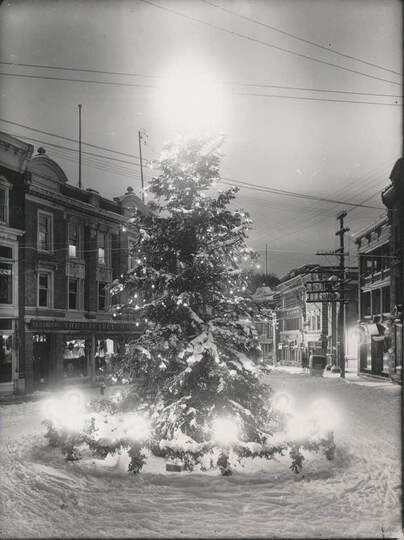

Dear Friends, Season's greetings to friends near and far from all of us at Historic Saranac Lake. I hope you enjoy this essay, inspired by both the joy and the sorrow of the holiday season. Best wishes for your good health and happiness in the New Year. Amy Catania Executive Director More than Memory December 21, 2021 by Amy Catania This time of year, as snow gently falls over the twinkling lights of our little town, Saranac Lake can seem pretty magical. The peace and joy of the season contrasts sharply with the suffering in the world. Each reality brings the other into focus, and I often think of those who have lost loved ones in this past year. When trying to make sense of loss, I come back to a little book my grandfather gave me some thirty years ago, The Bridge over San Luis Rey, by Thorton Wilder. The book tells the stories of five people whose lives were cut short by the collapse of a bridge in Perú. The final passage reads, “...soon we shall die and all memory of those five will have left the earth, and we ourselves shall be loved for a while and forgotten. But the love will have been enough; all those impulses of love return to the love that made them. Even memory is not necessary for love. There is a land of the living and a land of the dead and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.” We spend a lot of time at Historic Saranac Lake thinking about the land of the dead. One photo, one story at a time, we try to build bridges between the past and the present. Recently, a special visitor reminded us how important that work is and what it’s really all about. Earlier this month, Manuel Benero III visited Saranac Lake for the first time, traveling all the way from Mexico City. His grandparents, Pilar and Manolo, were two of the thousands of people from all over Latin America who came to Saranac Lake because of tuberculosis. Pilar came from Cuba with her sister who was ill with TB. Manolo came from Puerto Rico for the cure. Pilar and Manolo married in Saranac Lake in the 1920s. They settled in a brick house on Virginia Street, where they raised their two boys, Manny and Joe. Pilar taught piano lessons in their home. Her husband worked at the Troy Laundry and became a pillar of the community, joining the Lions Club, the Rotary, and the Fish and Game Club. He delivered dinners for Meals on Wheels. Their two sons were excellent students and talented hockey players. Both boys went on to serve their country in the armed forces. Years ago I researched the Spanish-speaking patients of Saranac Lake, and the story came alive for me when I found and interviewed Pilar and Manolo's grown children. So, I was thrilled to meet their grandson and make a connection to another generation of the Benero family. I shared photos and stories with Manuel about his grandparents' time here. Manuel explored the places around town his family had known. We found Pilar and Manolo's graves at the Catholic Cemetery. We called my friend Diane Seidenstein, and she described her love for her piano teacher. “My most vivid childhood memories are of my time with Mrs. Benero in her house,” she said. Pilar was beautiful, patient, and kind. Over the years, the Benero home was a warm, safe place for hundreds of Saranac Lake children. Having grown up overseas, Manuel doesn't remember ever meeting his grandparents. But by the end of his visit to Saranac Lake, I think he felt closer to them. Because it’s about more than memory. His grandparents' love is right here — as sure as this little book on my bookshelf, as strong as a small brick house on Virginia Street in the gently falling snow. ****

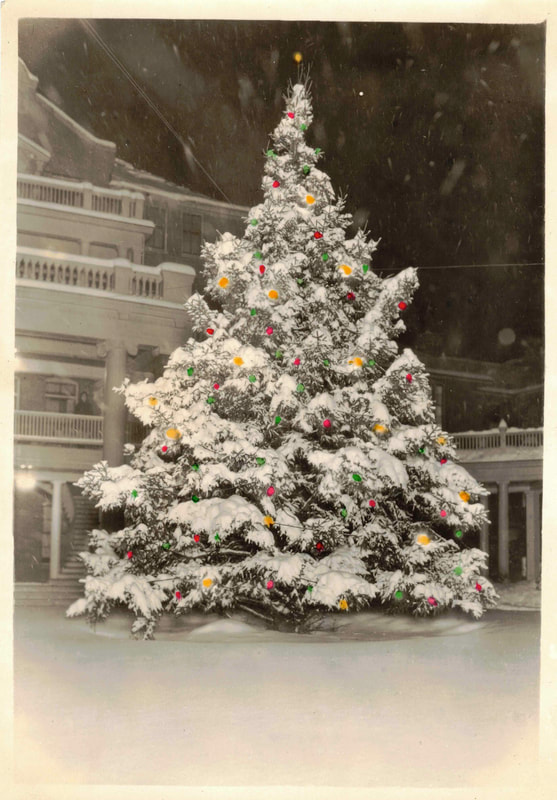

For Sabra By Amy Catania “The historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence” ― T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets Soon we will open a new exhibition at the museum called “Pandemic Perspectives.” The exhibit will highlight different experiences in Saranac Lake during the TB curing years, and visitors will be invited to make connections to life during COVID-19. Creating an exhibit is a team effort. Each person on our small staff brings a different set of skills from research, to writing, to design. Thanks to the expertise of our archivist and curator, Chessie Monks-Kelly, we draw upon our growing collection of artifacts, images, and documents. With help from trusty volunteers like Marty Rowley and Rob Russell and hardworking local businesses like Compass Printing and Stacked Graphics, it all comes together. This new exhibit is a simple concept: twelve panels, each labeled with one word like “gratitude” or “fear,” a photo, a short caption, a quote, and a question. Quotes from literature explore real and imaginary pandemics from the past. From The Plague, by Albert Camus, to The Birds, by Daphne du Maurier, literature reminds us that our struggles and triumphs are part of a vast human experience that extends across cultures and generations. Each panel may take no more than a minute to read, but we expect they will conjure up a wealth of reactions and questions. In May, we hired a new staff person, Mahala Nyberg, and she got right to work on the exhibit. Not knowing a cure chair from a stone pig, she brought fresh eyes to the project. One day, as she sorted through photos documenting the experience of COVID-19 in Saranac Lake, Mahala expressed astonishment at images of handmade signs posted in the windows of local businesses during the lockdown. She lived through the pandemic in her rural hometown, where there is no downtown. People drive to Walmart or Wegmans for what they need, and so, during the long spring of 2020, Mahala never saw a homemade sign in a local business wishing her and her neighbors well. The simple signs on the doors of friendly local businesses like the Dance Sanctuary, Nori's, the Community Store, and Lakeview Deli speak to a powerful sense of place we sometimes take for granted. Drawn by Saranac Lake’s strong sense of community, Ernest White II recently visited the village to record an episode for his popular travel show, “Fly Brother.” One rainy day in May, I joined a group of locals to walk around town with Ernest and his film crew. Ernest’s tour of the Adirondacks will ultimately be condensed down to a thirty-minute episode, so we knew most of what we showed him won’t make the cut. Seeing town from the eyes of a world traveler, it’s easy to notice the rundown side of Saranac Lake. We stood in Berkeley Green, eating soggy s’mores in the rain. There, in the space where the beautiful Berkeley Hotel once stood, it was hard not to think about all that’s been lost. The village doesn’t always look like such a great tourist destination, especially on a cold and rainy day. Still, Ernest seemed pleased with the spirit of the place. We talked about cure porches, hunting traditions, famous visitors, our museum expansion project, and the restoration of the Hotel Saranac. Mayor Rabideau helped him catch a fish.

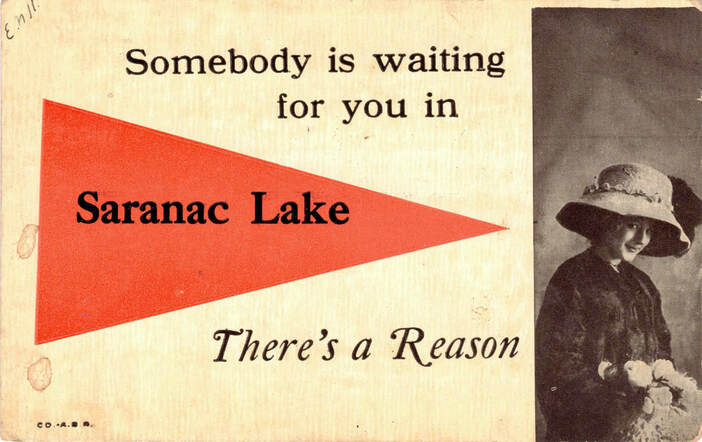

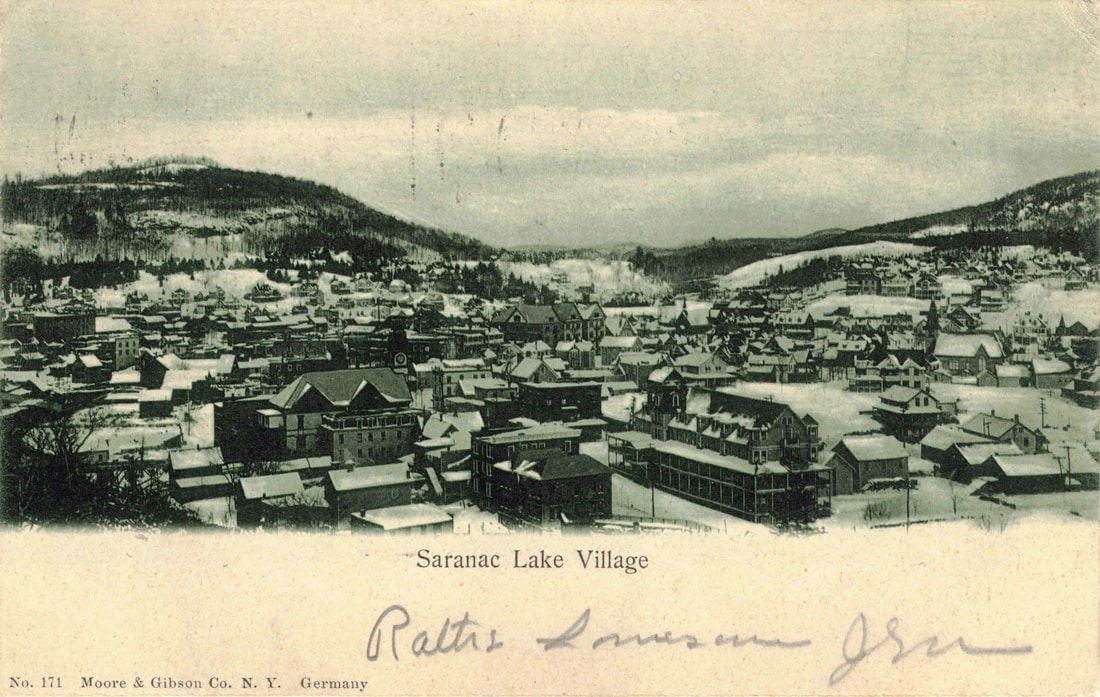

At the end of my interview, Ernest asked me what I have liked the most about living in Saranac Lake. I thought about those signs in the downtown windows in the last year, and I told him the truth, although it was absolutely the wrong answer for a tourism sound bite. Standing there in Berkeley Green in the rain, I answered simply, “Being a mom. Saranac Lake has been a great place to raise a family.” My answer I’m sure will hit the cutting room floor with a thud. But I am glad he asked me the question. It helped remind me of what is right here in front of my face, waiting to be seen with fresh eyes. Dear Friends, Separated from loved ones during the pandemic, many of us have been staying in touch with good old fashioned postcards. Americans’ love of postcards dates back to 1893, when the first souvenir postcards were sold at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The postcard craze caught on quickly. By 1915, millions of postcards changed hands. Many were carefully preserved in albums and displayed in homes across America. Before radio and television, postcard collections provided entertainment and a window into the wider world. Historic Saranac Lake recently acquired a wonderful album of some 80 postcards portraying the daily life of TB patients in Saranac Lake during the early 1900s. Over many years, Florence Wright carefully collected and preserved cards mailed from the booming health resort. One postcard, sent in 1909, summed up Saranac Lake at the time, "We leave here today, had a big time. The Village is just fine, lots of sick people here." In the early 1900s, postcards were printed in Germany by highly specialized printers, and the images are startlingly clear. Beautiful buildings appear in now empty lots, a horse pulls a pair of friends in a sleigh down Main Street, a speed skater takes a turn. At first, postal regulations prohibited writing on the flip side, so senders wrote messages over the image on the front. Eventually, rules changed and allowed for writing on the back, making for longer and more interesting messages. Looking at old postcards, one phrase at a time, human experience comes into focus, from the mundane to the deeply personal. Many of the cards from Saranac Lake are written by TB patients. They describe intense cold on cure porches and personal health facts like daily temperature readings and weight gain. Messages tend to be short, and many sentences are fragments. Yet there is often an easy familiarity between the sender and receiver. Many of the postcards are clearly written in the context of frequent exchanges of letters and cards. Just before WWI, the U.S. enacted tariffs that disrupted the postcard industry. Printing moved from specialized German companies to firms here at home that lacked the technology and expertise to create clear images. Inferior, cheap postcards flooded the market, and the postcard craze started to wane. Still, postcards continued to be purchased and shared, documenting daily life in the health resort. Florence’s postcards show that one hundred years ago, people were coping with the personal and public health threat of tuberculosis in many of the same ways we are responding to the pandemic today, with a mix of worry, fear, and sadness, but also hope, gratitude, and love. Each postcard is a poignant statement of the human need to connect with one another. In 1908, one person wrote to a friend in Cazenovia, “I can't help but be a bit lonesome. Still people are very kind to me. Be sure and write soon." This summer we will unveil a new exhibit titled, “Pandemic Perspectives,” exploring connections between our experience of the current pandemic and life in Saranac Lake during the TB years. The exhibit will include some of Florence’s postcards, and visitors will be invited to write their own notes describing what they have felt in the past year. We hope you will come drop us a line! Yours truly, Amy Amy Catania Executive Director RESOURCE: “Wish You Were Here!: The Story of the Golden Age of Picture Postcards in the United States,” by Fred Bassett, Senior Librarian, Manuscripts and Special Collections, New York State Library. 2016.

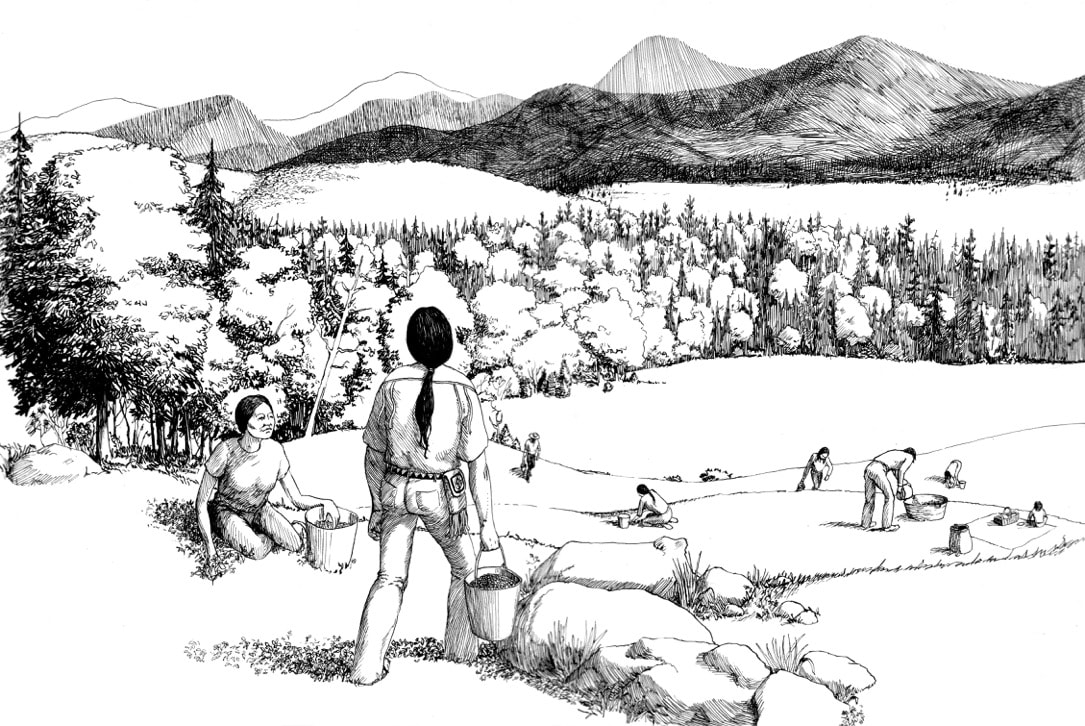

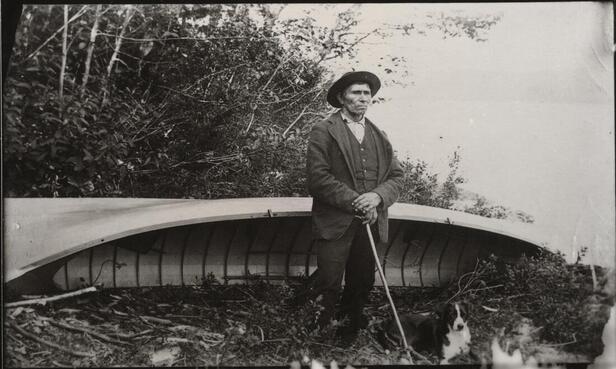

by Amy Catania These days it seems like everyone wants to call the Adirondacks home. During the pandemic, closed-in city spaces have lost their allure. It’s a repeat of Saranac Lake’s tuberculosis years, when tens of thousands of people came here from around the world in search of the fresh air cure. When you want to avoid germs, a place with more trees than people is a good bet. Adirondackers have a long love-hate relationship with outsiders. As the 20th century began and the TB industry picked up speed, strangers poured into the village. As much as TB represented a way to put food on the table, not all locals were thrilled with the changes newcomers brought. Guide and boatbuilder Fred Rice wrote a manuscript in 1952 decrying the development of the village as a health resort. During his father’s lifetime, as logging dried up, the business of wilderness tourism was flourishing. Mr. Rice argued this would have been the preferred pattern of development, “…persons not connected with the health interests have never felt particularly grateful to the doctors for changing the young pleasure resort into a health resort,” he wrote. Fred Rice’s Saranac Lake of 1952 was coming to look a lot like it does today — a village paved for cars, strung with wires, teeming at times with city people. It’s easy to look back at the quieter times of the 1800s as the beginning of our history. We tend to think of young Fred Rice, his dad, and the tough old Adirondack guides like them, as the original Adirondackers. Such a view ignores the history of people who lived here for thousands of years. Written accounts by early white settlers document the Adirondacks as a homeland and an important place of resource for many indigenous people. But as white people sank roots and claimed their future here, they re-wrote history to claim the past too. By 1921, historian Alfred Donaldson was writing that Indians just passed through the area. To the present day, a dearth of archeological studies has perpetuated the myth that Native Americans did not consider the Adirondacks home. At Historic Saranac Lake, we have often repeated this mistaken version of history. Drive 15 minutes outside of the village, and you will find an amazing little museum that presents a much longer, more complete view of the past. Founded in 1954, Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center has been run by three generations of the Mohawk of Akwesasne Fadden family. There, you will discover that the Adirondacks were home to Algonquian-speaking and Iroquoian-speaking people since before 9000 BCE. The distinct culture of the Haudenosaunee formed within a vast territory that included much of New York State and the Adirondacks. Stories handed down across countless generations document the Adirondacks as a treasured homeland, a place of refuge, and a source of resources from fishing, hunting, trapping, mining, tapping trees, ice fishing, and the harvesting of medicinal plants. At Historic Saranac Lake, we talk a lot about the last 150 years, but the human history of the Saranac Lake region goes back some 80 times farther! A fluted arrowhead found recently on St. Regis Lake is estimated to be some 13 thousand years old. At the top of the high peaks, Potsdam University Archaeologist Tim Messner found a piece of worked flint to make stone tools. People were here, calling this place home, hunting caribou across glaciers, before there were trees. It turns out, Fred Rice and his father were also interlopers, just a skip away in time from today’s city people looking for parking by Mount Baker. Not only have we dismissed thousands of years of Native American history, we have ignored or diminished the presence of Native Americans in recent history to the present day. As the Adirondacks developed, Native Americans were forced to adapt as old livelihoods were no longer sustainable. Lumber operations, land takeovers by private owners and the state, and hunting for sport, all made for less game. Some Indians turned to guiding. They imparted their deep knowledge of the woods and waters to white settlers, making their survival possible. Native peoples survived as entrepreneurs, and in the towns and hamlets of the Adirondack Park, they have continued to maintain their cultural traditions. As the weather warms, and local trails and lakes fill up with out-of-towners, we should keep in mind that few of us are rightful owners of these mountains. Native American people would wisely say that no one owns the land; at best we are merely stewards of this place we call home. SPECIAL THANKS:

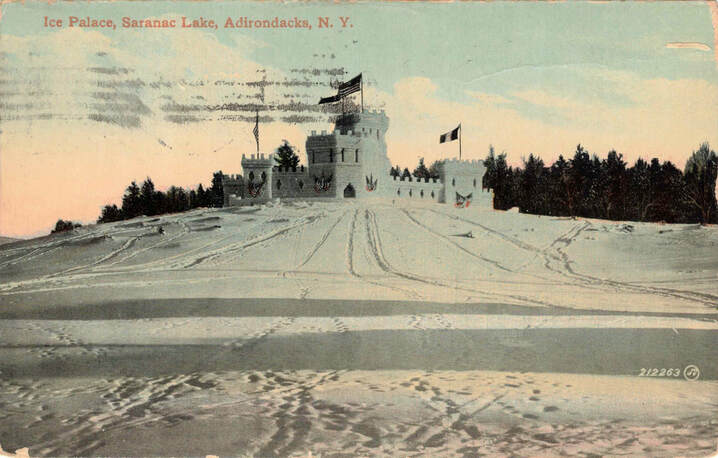

John Fadden, Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center Iakonikonriiosta, the Akwesasne Cultural Center Tim Messner, SUNY Potsdam Jen Krester, the Wild Center Humanities New York. RESOURCES: "Mohawk Presence in the Adirondacks" by John Fadden “Hidden Heritage” by Curt Stager (Adirondack Life, June 2017) Rural Indigenousness by Melisa Otis (Syracuse University Press, 2018) “A History In Fragments” by Lynn Woods (Adirondack Life November/December 1994) by Amy Catania This month, one block at a time, an ice palace emerged again on the shore of Lake Flower. If you had the chance to stop by, you may have felt its warm embrace. The massive ice blocks of the palace remind me of the stone walls of Machu Picchu. Relying on a system of communal labor called mit’a, the Inca built enormous stone structures and highly engineered roads and bridges. Each citizen who could work was required to donate a number of days of their labor to cultivate crops and build public works. Historians of ancient Peru trace the ways the mit’a system forged a complex society. Working together, people developed friendships and bonds of reciprocity that served the common good throughout the year. Saranac Lake has its own form of mit’a. Winter Carnival brings together individuals from all walks of life, all ages, political persuasions, types of jobs, and personalities. Building an ice palace or a parade float isn’t always fun. We disagree about costumes, decorations, and dance moves. Like siblings we squabble, but we emerge on the other side laughing. Just like the blocks of the ice palace, one person at a time, carnival comes together. Eventually the palace melts down to a pile of rubble like an Incan ruin. But when it’s time to argue about an issue relating to the school district or village politics, having survived the dry run of carnival, we make it through together. A community net is forged. When your luck takes a turn, it is there to catch you. At Winter Carnival time, I think of this illustration by Mildred McMaster Blanchet. Milly left behind beautiful artwork and lively poems that belie a life marked by its share of hardship. A trained artist who came to Saranac Lake with TB, she met her husband Dr. Sidney Blanchet when they were both patients at Trudeau. Dr. Blanchet served as Dr. E. L. Trudeau’s personal physician. He was well respected and deeply loved by his patients. Milly and Sidney settled in the village and had three children. The community reached out to help the Blanchet family more than once. In the winter of 1933, the oldest Blanchet boys, Gray and David, fell through thin ice while skating on Lake Flower. The Ogdensburg Journal reported, “Their screams were heard by a group of boys on the shore. With presence of mind the youths quickly grabbed planks, and ropes at a nearby garage and rushed to the aid of the lads in the freezing water.” Thanks to the heroic efforts of young Saranac Lakers, including Charlie Keough and Paul Duprey, the boys survived. Four years later, tragedy struck again and didn’t miss. During the Depression, many of Dr. Blanchet's patients could not pay for care. He often treated them for free, resulting in his own bankruptcy. Dr. Blanchet fell into a deep depression and tragically took his life. Milly must have felt the world crumble under her feet. But the community net reached out. She was offered a place to live at the Trudeau Sanatorium and hired as an occupational therapist at the workshop. She taught painting, knitting, crewel work, and hand embroidery. Piece by piece, Milly re-built her life by helping others.

Eventually, thanks in part to the heroic ice rescue of 1933, Milly became a proud grandmother of ten. She retired to a senior center in Massachusetts where she created a craft room for the residents. Her granddaughter Sylvia remembers, “The walls were lined with shelves of every kind of art supply. There was a great table in the center of the room that was always filled with busy, happy people when Grand Milly was in attendance. She would mentor whoever was in need of attention and encourage every project. I saw people hooking rugs, knitting, doing needle point, and painting among other things. It was as if the people in the room were her garden and everyone there would blossom through her kind and gentle presence.” In Saranac Lake, the workshop that shaped Milly’s life still stands. For a brief time, an ice palace emerged on the shore of Lake Flower. Sadly, this year's palace was demolished early to avoid gatherings during the pandemic, but come back next winter for a warm hug. by Amy Catania Seeking some historical perspective on the current pandemic, Historic Saranac Lake recently hosted an imaginary panel discussion at St. John’s in the Wilderness Cemetery. Three generations of Doctors Trudeau shared their thoughts on change and continuity in science and public health. CAST OF CHARACTERS

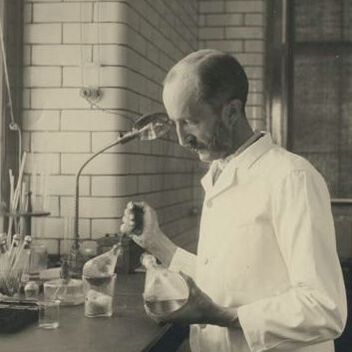

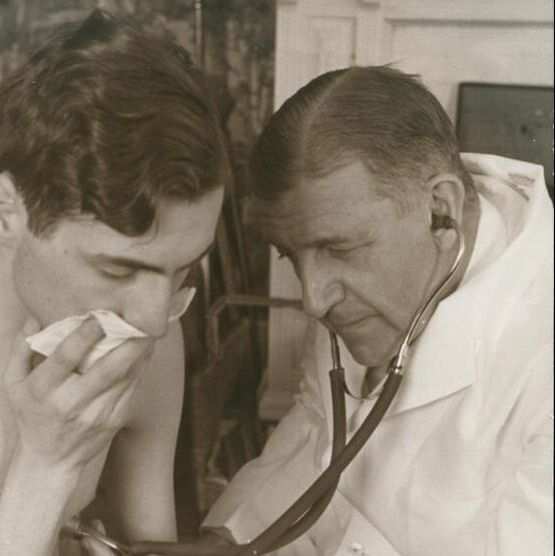

MODERATOR: In your lifetimes, each of you witnessed major advancements in the scientific understanding and medical treatment of infectious disease. Does it surprise you to see a new virus set the world back on its heels? DOCTOR 2: Indeed, it is a shock. Today’s situation reminds me of the flu that I saw when I served on military base during the Great War. Basic nursing care and sanitary measures were our only weapons. DOCTOR 1: In my time, huge advancements were made in science and medicine, so it is surprising to see the mess we are in with this new virus. 150 years ago, I came to Saranac Lake fighting "consumption," a disease that was killing 1 in 7 people in our country. We had no idea what caused it or how to cure it. Then, in 1882, Dr. Koch discovered the tubercle bacillus under the microscope in Germany. It seemed science would save the world from infectious disease. DOCTOR 2: When the antibiotic treatment for TB was perfected in the 1950s, it was a miracle. Many of my patients who had been sick for years suddenly got out of bed and returned to the living. DOCTOR 3: Thanks to groundbreaking advancements like antibiotics and the polio vaccine, there was great optimism. U.S. Surgeon General William Stewart announced in 1969 that the time had come to “close the book on infectious disease.” DOCTOR 1: I can understand that perspective. “Optimism in Medicine” was the title of my last public speech! MODERATOR: Yet tuberculosis continues as a major public health threat, even now. And here we are with a new virus wreaking havoc around the world. What went wrong? DOCTOR 1: Looking back on my early struggles in the laboratory, I knew then that microbes are tricky little buggers. It is no wonder that they continue to outwit us. DOCTOR 3: In the 1960s, Eastern Europe was experiencing a resurgence of TB. Some doctors from the Soviet Union visited Saranac Lake to learn about our old surgical methods for TB. It drove home for me that science isn’t a straight trajectory. Microorganisms keep evolving. Overused and misused, antibiotics are losing their effectiveness. Some 1.5 million people are expected to die of TB in this new year! Scientific development of new antibiotics is woefully underfunded today. DOCTOR 1: Research dollars flow to where there is money to be made, not necessarily where human health most needs the research. I founded my Saranac Laboratory in 1894 as purely a research laboratory, with no commercial side to it. Soon I realized the difficulty of that model. DOCTOR 3: Still, I have such hope in science! In 1964, I opened the doors of the new Trudeau institute for the first time. I was so proud on that day, and I am thrilled to see Trudeau Institute still with us, carrying out important research. Science holds great promise. Just look at the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines! DOCTOR 1: Today's vaccines are an achievement that I could have never imagined back in the early days when my microscope was lit by natural light. But it must be a two-pronged approach — science and public health. MODERATOR: What do you think about the state of the public health system today?

DOCTOR 3: Under-resourced systems are straining to care for the sick, administer the vaccines, and prepare for the next disease. The lack of attention to public health is not new. In my time, as we came to rely more on pharmaceuticals, the holistic sanatorium model — buttressing the immune system with a long-term approach to wellness — fell by the wayside. DOCTOR 2: I remember when the last patient left the sanatorium in 1954. It was a sad day for Saranac Lake, but a hopeful day for humanity. We thought then that the magic bullet of pharmaceuticals would simplify patient care and ultimately take the place of many prevention measures. It hasn’t been that easy. DOCTOR 1: It’s been true for a long time — more lives are saved by public health measures than by medical care. Population density, poor sanitation, unventilated spaces, poverty, stress … all of these ills of the modern world contribute to infectious disease. (Yes, the late 1800s were “modern” to us then!) Addressing those conditions was (and is!) essential to improving human health. The world has taken shortcuts around simple public health measures. Coronavirus proves the danger of that approach. DOCTOR 2: With each returning disease, like plague and Cholera, to new ones like HIV, Ebola, SARS, and COVID-19, public funding for emergency response and prevention surges, but then it declines again. MODERATOR: Today's virus isn’t just hitting poor countries hard. Wealthy countries like the U.S. are struggling too. What’s going on? DOCTOR 1: COVID-19 reveals that the same deep inequalities that bred the rise of TB in the 1800s are still with us. DOCTOR 2: It’s a terrible tragedy. I read that on average, each victim of COVID-19 has lost 13 years of life. Blacks and Hispanics are more than twice as likely to die of the disease. But many turn a blind eye. Many people doubt science and medicine and distrust their fellow citizens. Political divisions, exacerbated by the pandemic, are threatening our democratic system. DOCTOR 3: Disease doesn’t have to sow division. There is another path. Look how Saranac Lake came together as a community that cared for the sick with compassion. DOCTOR 1: Empathy was at the heart of our work at Saranac, and the world needs more of it now. I never hired a nurse, orderly, or doctor who did not have that essential quality. I am proud of today’s heroes in medicine and science. Their courageous work during this difficult time reminds me of a favorite phrase, “To cure sometimes, to relieve often, to comfort always.” Sources and Acknowledgements - Epidemics and Society by Frank Snowden, Yale University Press, 2019. - Covid-19 age expectancy statistic: January 2021 "Harper’s Index," Harper's Magazine, Stephen Elledge, Harvard Medical School. - Special thanks for input from Laura Ettinger, Ph.D., Associate Professor of History at Clarkson University and Dr. Tony Holtzman, Emeritus Professor of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins University. by Amy Catania "Strange, isn't it? Each man's life touches so many other lives. When he isn't around he leaves an awful hole.” — It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 This is a good time of year to watch It’s a Wonderful Life. Set in a fictional town in upstate New York called Bedford Falls, the movie tells the story of a man named George Bailey who discovers how much his life matters. The movie brings to mind the wonderful life of Saranac Laker, Alton “Tony” Anderson. Tony Anderson fell ill with tuberculosis while working as a toolmaker in Southington, Connecticut. As a member of the Masons, he received financial help to come to Saranac Lake for treatment in 1919. “I came here to die,” Tony used to say. Facing death, Tony received a gift, a chance to imagine the world without him. He made his home here and dedicated his life to giving back. He served as village mayor for nine terms. He worked as the volunteer ambulance driver and as a plane spotter on top of the Hotel Saranac during the war. He was a member of the Masonic Lodge, the Elks Club, the Rotary, the Boat and Waterway Club, the hospital board, and the blood bank. Mayor Anderson could always be seen around town, no matter the temperature, in his sport coat and tie, doing the informal business of holding the village together, one personal relationship at a time. He was a Republican in a time when political party didn’t matter much in small town politics. People voted for Tony time and again, because he was a good man who worked hard for the people of Saranac Lake. Mayor Anderson had a delightful, quiet sense of humor. He did the right thing without apology. If you needed something, he was there. The gem of Tony’s eye was the beautiful Pontiac Theatre. The theater had the largest screen in upstate New York, an orchestral organ valued at $12,000, velvet curtains, and gorgeous chandeliers. It wasn’t just a theater; it was an experience. Famed theatrical agent William Morris, here with his own case of TB, brought some of the most famous talent of the day to perform benefit shows at the Pontiac. Tony Anderson first worked as an usher in the balcony, which was reserved for TB patients. He went on to a long career as theater manager. Tony was always there at the door, warmly greeting each patron. After the Catholic Church burned, Tony opened the theater for Sunday services. Parishioners gave him the friendly appellation, “Father Anderson.” The business of managing the theater was hard work, and Tony liked to say that he “never missed a day and never saw a movie.” He kept a record of the date of each winter’s first snowfall on the doorframe of his little office under the theater stairs. Each afternoon, Tony went home to his modest house on South Hope Street and sat on his porch in a cure chair. “Best seat in the house,” he called it. After his afternoon rest, he would go back to the theater for the shows. Tony’s wife Helen is remembered as a lovely person. She took care of the books at Newman and Holmes hardware store. They had two children, Charlene and Bailey. Saranac Lake in the 1950s was a picture postcard of Bedford Falls. Everyone knew each other. Kids played together outside through all seasons. Downtown shops bustled year-round. The Adirondack Daily Enterprise was five times thicker than it is today. The theater, the radio station, civic organizations, and places of worship knitted the community together. Like the shadow of death cast by tuberculosis, the horrors of WWII inspired an appreciation for life and a sense of civic responsibility. But forces were afoot that were beginning to devastate small towns around the country. Everywhere, industry and manufacturing were closing up shop. In Saranac Lake, the TB business came to an end. Jobs dried up and families left. Across America, suburban development was eroding downtown retail. Television offered solitary entertainment that took the place of public activities like going to the movies. By the late 1960s, Tony Anderson’s beloved theater had fallen on hard times. The impeccably dressed ushers were gone, and, much to Tony’s chagrin, on Wednesday nights the Pontiac was showing titillating foreign films that reflected changing social mores. It seemed that only the bars were prospering. The town was on track to become like Pottersville, Bedford Falls’ evil twin in the movie. The forces that were changing the village were bigger than the efforts of the good men and women of Saranac Lake. But things have a way of coming full circle. Many former TB patients credit their brush with death for shaping their sense of civic duty. As we emerge from a global pandemic, perhaps we have more than one Tony Anderson in the making. Good people and places are still with us. Cross the bridge by the Left Bank Cafe. Turn the corner, and walk past the Hotel Saranac, the museum, and the library. You just might see glimmers of Bedford Falls. Sadly, some things are indeed lost forever. On December 19, 1978, a massive fire devastated the Pontiac Theatre. Three years after the fire, Saranac Lake’s longest serving mayor died at the age of 82. The Adirondack Daily Enterprise obituary stated, “Will Rogers said, 'I never met a man I couldn't like.' With apologies for the paraphrasing, we say, 'We never met anyone who didn't like Tony Anderson.’” It’s true, no man is a failure who has friends. George Bailey and Tony Anderson had a lot of them, regular people who in small ways make up the wonderful life of a small town. George Bailey’s friends in Bedford Falls bring to mind the regular people of Saranac Lake who look out for each other — people like Ernie the taxi driver, Bert the policeman, Mary the devoted wife and mother, Mr. Gower the pharmacist, Martini the barkeep, Harry the war hero, the woman at the bank who asks for only $17.50, and Clarence the angel. “Merry Christmas, movie house! Merry Christmas, Emporium! Merry Christmas, you wonderful old Building and Loan!”

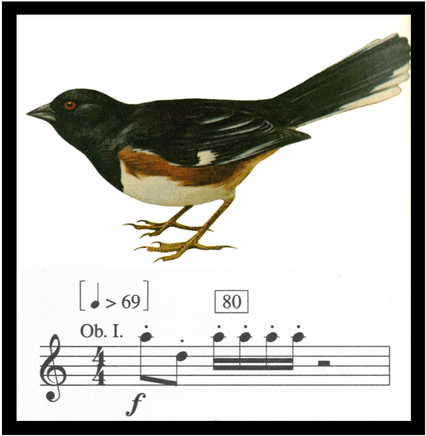

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays, Saranac Lake. -- Special thanks to those who shared their memories for this story: Chris Brescia, Jan Dudones, Jim Griebsch, Bunk Griffin, Howard Riley, Jim and Keela Rogers, and our dear friend, Natalie Leduc, who, on December 8 came to the end of her truly wonderful life. We won’t be the same without her. by Amy Catania "I have been so upset by world events that my mind has been almost completely paralyzed.” — Béla Bartók In the midst of the dark days of World War II, a frail man named Béla Bartók came to Saranac Lake for his health. Although he was one of the greatest composers in human history, many Saranac Lakers might have seen him as just another invalid, tiny and pale, wrapped in his dark cape against the cold Adirondack weather. Bartók and his second wife Ditta fled their native Hungary eighty years ago, as fascism and antisemitism swept across Europe. He had dedicated his life not only to composing, but also collecting and arranging the folk music of Eastern Europe. Nazi Germany was threatening to erase the cultures of the Roma and other peasant peoples of the region. In the face of such terror, Bartók was depressed, impoverished, and sick with a form of leukemia that acted like tuberculosis. He and his wife moved from one cramped, loud, New York City apartment to another. He had ceased composing. In the summer of 1943, the Bartóks found refuge in Saranac Lake. Here, wrote his son Peter, "he found the peace and tranquility suitable for composing…. My father was obviously contented; his surroundings were as spartan as the interior of a Hungarian peasant cottage -- a reminder of a world with such fond associations for him.” Bartók spent three summers in Saranac Lake, where the quiet and natural environment inspired some of his greatest works — the Concerto for Orchestra, the Viola Concerto, and the Third Piano Concerto. In his music, he integrated peasant melodies of Eastern Europe with the birdsong of the Adirondacks. Here, under the cloud of terrible world events, he found a measure of hope. The cabin off of Riverside Drive, where Bartók stayed the last summer of his life in 1945, was saved from demolition thanks to a Romanian pianist named Cristina Stanescu. She had come to Saranac Lake to perform with the Gregg Smith Singers one summer some thirty years ago. While staying at Fogarty’s Bed and Breakfast, she learned about the decrepit cabin down the street where Bartók once stayed. The composer was a hero to Cristina. When she was just six years old, her first teacher in Romania had taught her Bartók’s music even though it was banned under Communism. To Christina’s teacher, Bartók represented friendship among the peoples of Eastern Europe, and his modernist compositions had become a symbol in Europe of anti-fascist resistance.

Cristina Stanescu raised the alarm to save the cabin. Emily Fogarty, Mary Hotaling, George Pappastavrou, Lex Dashnaw, and Doug March took up the cause, and they worked with a team of volunteers and musicians to raise the funds to save the cabin. Today Historic Saranac Lake provides tours of the Bartók Cabin in the summers, and many interesting people from around the world visit each year. One recent visitor to the cabin was Brian Ward. His grandmother, Corneila Hamvas, fled from the Nazis to the United States with her Jewish family. Back in Budapest, when Cornelia was seven years old, Béla Bartók taught her how to play the piano. This fall, standing in the humble cabin with Cornelia’s grandson, the past felt very close at hand. We listened for Bartók’s birds, calling in the woods. “My own idea… is the brotherhood of peoples, brotherhood in spite of wars and conflicts, I try -- to the best of my ability -- to serve this idea in my music; therefore, I don't reject any influence, be it Slovakian, Romanian, Arabic, or from any other source.” — Béla Bartók by Sunita Halasz While the coronavirus pandemic rages like a figurative wildfire all over the world in 2020, actual wildfires are setting horrific records out west this year. The combined acreage of burned area surpasses the size of the state of New Jersey. The loss is not just to forest land, but to homes and businesses, and in some cases whole communities have been apocalyptically reduced to ash. It’s hard to imagine that similar widespread forest fires once burned the Adirondacks around the turn of the twentieth century. Flames spread throughout the Park, and ash from Adirondack fires fell as far away as Albany, and smoke was reported in New York City. Fires in 1903 and 1908 were particularly widespread in the North Country. 1903 was a dry year for the entire Northeast. In the Adirondacks, snowfall was less than average, and from April to June that year, only 0.2 in. of rain was recorded. In 1904, W. F. Fox wrote in “Forest Fires of 1903,” a bulletin of the NYS Forest, Fish, and Game Commission: The line of the New York Central from Fulton Chain to Mountain View was bordered with smoke and flames, except on the eight-mile stretch through the private preserve of Dr. William Seward Webb, where a large number of patrols were employed at his expense to follow each train, night or day, and extinguish the locomotive sparks that fell along the road. Many Adirondack fires were caused by live coals that escaped from unscreened locomotive stacks and fell on dry, vertical slash in the heavily logged forests along railroad lines, though Professor Emeritus of Paul Smith’s College, Dr. Michael Kudish, estimates that only about eleven percent of fires were caused by trains. More commonly, forest fires were caused by escaped campfires and brush-clearing fires, and the furnaces associated with mining operations in the Park. With the exception of mining furnaces, campfires and burning brush piles remain the top threat for wildfire in the Adirondacks today. One of the largest acreages burned during the 1903 fire season was around Lake Placid in a fire started by high winds fueling a burning brush pile. That fire spread into the High Peaks and is the one that burned down Henry Van Hoevenburg’s Adirondack Lodge. Mt. Baker in Saranac Lake burned in 1903 and again in 1908 when dry conditions and logging slash once again proliferated throughout the region. The 1908 fire spread east to McKenzie Mountain and threatened the village of Saranac Lake, as well, but it ultimately remained contained to the wilderness. In 1914, the Saranac Lake Fish and Game Club ordered 15,000 Scots pine (also called Scotch pine) grown at the State Nursery at Saranac Inn, at a price of just $60 for the whole load, and the trees were planted by a volunteer force of local men and Saranac Lake High School boys.

A May 15, 1914 article in the Lake Placid News states, “It is not expected that the 15,000 trees will make much of an impression on the stony sides and summit of Baker...” The prediction was wrong! Those Scots pines are still very visible as a dark green patch in all seasons up on Baker Mountain today. After fires burned over 400,000 acres in the Forest Preserve in 1903, and nearly 300,000 acres in 1908, strict laws were enacted that set up a patrol of railroad properties, forced railroads to use petroleum for steam locomotive fuel instead of coal or wood, punished those responsible for escaped fires, enabled the building of fire towers (the first fire tower built in the Adirondacks was on Mt. Morris in Tupper Lake in 1909), and gave executive power to the Governor to close the Forest Preserve to recreationists in times of high fire risk. The widespread Adirondack fires in the early part of the twentieth century were an anomaly due to the convergence of several factors including climate and fuel loads. Fire in northeastern forests has been historically absent, as shown by fossil pollen and charcoal records which estimate a fire return frequency of many hundreds to thousands of years, due to swift leaf litter decomposition, low wind risk, widely and rapidly varying topography, and the fire-resistant nature of northern hardwoods. This doesn’t mean, however, that fires can’t happen here today. We must remain vigilant and follow local regulations about campfires, burning brush, proper disposal of cigarette butts, and so forth. The first time I ever visited Vermontville it was to research the site of the 1991 fire near Kate Mountain Park that burned 300 acres. I was a graduate teaching assistant for an ecology course at Cornell University and, of all the places we could have visited in the state, we went to Vermontville because it was such an excellent opportunity to observe post-fire vegetation recovery. Now I live in Saranac Lake and coach our homeschool soccer team at Kate Mountain Park each fall, so I am watching the forest there grow a little taller each year and seeing the plants in the understory get a little more shaded out. But like we are seeing out west, slight changes in climate, exacerbated by careless actions of humans, can have drastic damaging ripple effects that will be felt for decades. Images: -Ampersand Mountain fire tower, c. 1960. Photograph by Donald Gunn Ross, courtesy of Julie Ross. -Mount Baker, undated. Library of Congress photo. |

About us

Stay up to date on all the news and happenings from Historic Saranac Lake at the Saranac Laboratory Museum! Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

Historic Saranac Lake at the Saranac Laboratory Museum

89 Church Street, Suite 2, Saranac Lake, New York 12983

(518) 891-4606 - [email protected]

89 Church Street, Suite 2, Saranac Lake, New York 12983

(518) 891-4606 - [email protected]

Historic Saranac Lake is funded in part by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature,

and an Essex County Arts Council Cultural Assistance Program Grant supported by the Essex County Board of Supervisors.

and an Essex County Arts Council Cultural Assistance Program Grant supported by the Essex County Board of Supervisors.

© 2023 Historic Saranac Lake. All Rights Reserved. Historic photographs from Historic Saranac Lake Collection, unless otherwise noted. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed