|

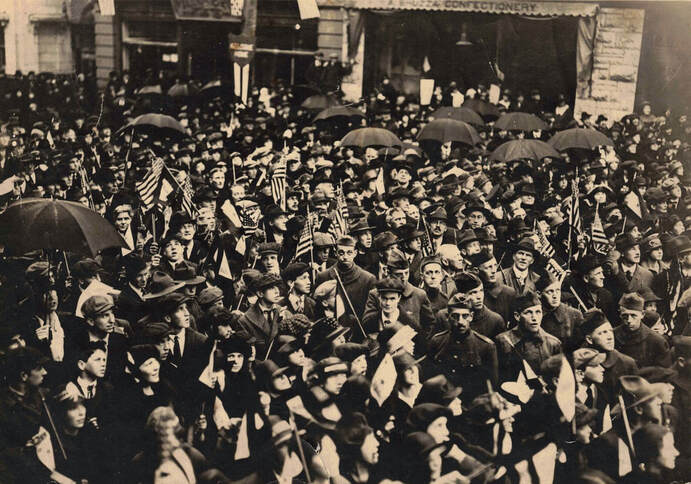

We're joining in with the Museum of the City of New York for a virtual #MuseumThanksgivingParade! These parade shots come from Winter Carnivals past and present, from 1913 to 2019!

Learn more about Winter Carnival parades throughout history on our wiki.

1 Comment

Dr. Edward R. Baldwin prepares to carve a turkey in the Baldwin House on Church Street, most likely for a Thanksgiving meal in the 1920s. Dr. Baldwin came to Saranac Lake with tuberculosis after medical school, and was hired by Dr. Edward L. Trudeau to work at the newly built Saranac Laboratory. He eventually served as Director of the Laboratory, along with many other scientific and civic pursuits. Happy Thanksgiving Week!

Learn more about Dr. Baldwin on our wiki: https://localwiki.org/hsl/Edward_R._Baldwin Historic Saranac Lake is in the process of a major image cataloging project with support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. We will be sharing fascinating images of life in Saranac Lake throughout history in the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, but our fans online will get the first peek at the images! Have a request for images you want to see? Let us know! [Historic Saranac Lake Collection, TCR 448, courtesy of Barbara Baldwin Knapp.] Our next Veteran-themed Tuberculosis Thursday feature is John Baxter Black! Black served in World War I, and was in active service in France when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1918. He was sent to Saranac Lake to cure his intestinal tuberculosis, and his health improved over the course of five years. Unfortunately, he developed an infection following a surgical procedure in Montreal, and died on May 16, 1923.

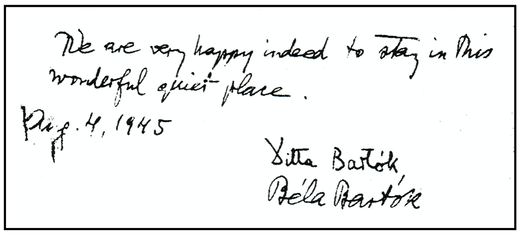

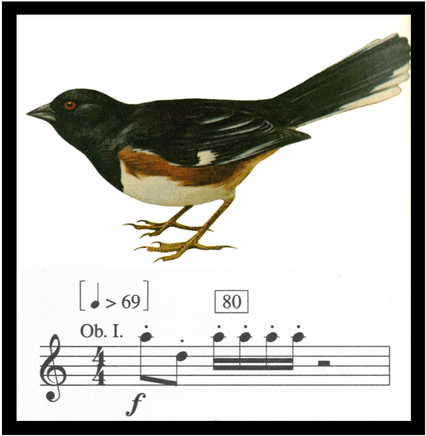

Following his death, the Black Family of Mansfield, Ohio donated the addition of a new wing on the Saranac Laboratory, including the John Black Memorial Library. This portrait of John Baxter Black in repose during his cure hangs in the John Black Room at the Saranac Laboratory Museum. Learn more about Black's time in Saranac Lake on our wiki. by Amy Catania "I have been so upset by world events that my mind has been almost completely paralyzed.” — Béla Bartók In the midst of the dark days of World War II, a frail man named Béla Bartók came to Saranac Lake for his health. Although he was one of the greatest composers in human history, many Saranac Lakers might have seen him as just another invalid, tiny and pale, wrapped in his dark cape against the cold Adirondack weather. Bartók and his second wife Ditta fled their native Hungary eighty years ago, as fascism and antisemitism swept across Europe. He had dedicated his life not only to composing, but also collecting and arranging the folk music of Eastern Europe. Nazi Germany was threatening to erase the cultures of the Roma and other peasant peoples of the region. In the face of such terror, Bartók was depressed, impoverished, and sick with a form of leukemia that acted like tuberculosis. He and his wife moved from one cramped, loud, New York City apartment to another. He had ceased composing. In the summer of 1943, the Bartóks found refuge in Saranac Lake. Here, wrote his son Peter, "he found the peace and tranquility suitable for composing…. My father was obviously contented; his surroundings were as spartan as the interior of a Hungarian peasant cottage -- a reminder of a world with such fond associations for him.” Bartók spent three summers in Saranac Lake, where the quiet and natural environment inspired some of his greatest works — the Concerto for Orchestra, the Viola Concerto, and the Third Piano Concerto. In his music, he integrated peasant melodies of Eastern Europe with the birdsong of the Adirondacks. Here, under the cloud of terrible world events, he found a measure of hope. The cabin off of Riverside Drive, where Bartók stayed the last summer of his life in 1945, was saved from demolition thanks to a Romanian pianist named Cristina Stanescu. She had come to Saranac Lake to perform with the Gregg Smith Singers one summer some thirty years ago. While staying at Fogarty’s Bed and Breakfast, she learned about the decrepit cabin down the street where Bartók once stayed. The composer was a hero to Cristina. When she was just six years old, her first teacher in Romania had taught her Bartók’s music even though it was banned under Communism. To Christina’s teacher, Bartók represented friendship among the peoples of Eastern Europe, and his modernist compositions had become a symbol in Europe of anti-fascist resistance.

Cristina Stanescu raised the alarm to save the cabin. Emily Fogarty, Mary Hotaling, George Pappastavrou, Lex Dashnaw, and Doug March took up the cause, and they worked with a team of volunteers and musicians to raise the funds to save the cabin. Today Historic Saranac Lake provides tours of the Bartók Cabin in the summers, and many interesting people from around the world visit each year. One recent visitor to the cabin was Brian Ward. His grandmother, Corneila Hamvas, fled from the Nazis to the United States with her Jewish family. Back in Budapest, when Cornelia was seven years old, Béla Bartók taught her how to play the piano. This fall, standing in the humble cabin with Cornelia’s grandson, the past felt very close at hand. We listened for Bartók’s birds, calling in the woods. “My own idea… is the brotherhood of peoples, brotherhood in spite of wars and conflicts, I try -- to the best of my ability -- to serve this idea in my music; therefore, I don't reject any influence, be it Slovakian, Romanian, Arabic, or from any other source.” — Béla Bartók Continuing our Veteran-themed Tuberculosis Thursday posts, today we're highlighting the Arlington Hotel! The hotel was located on the northeast corner of Broadway and Bloomingdale Avenue, and was built sometime between 1895 and 1899. After the hotel abruptly closed in 1919--the manager disappeared with anything moveable and of value--it was reopened as a vocational school for tubercular Veterans of World War I. It opened with classes on salesmanship and law, and offered commercial and general education courses. Ernie Burnett remembered it as the first meeting place for the "Vets' Post" in his "Our Town" column in 1954.

Read more about the history of the Arlington on our wiki. [Photograph of the Arlington Hotel, courtesy of the Adirondack Research Room at the Saranac Lake Free Library.] by Sunita Halasz While the coronavirus pandemic rages like a figurative wildfire all over the world in 2020, actual wildfires are setting horrific records out west this year. The combined acreage of burned area surpasses the size of the state of New Jersey. The loss is not just to forest land, but to homes and businesses, and in some cases whole communities have been apocalyptically reduced to ash. It’s hard to imagine that similar widespread forest fires once burned the Adirondacks around the turn of the twentieth century. Flames spread throughout the Park, and ash from Adirondack fires fell as far away as Albany, and smoke was reported in New York City. Fires in 1903 and 1908 were particularly widespread in the North Country. 1903 was a dry year for the entire Northeast. In the Adirondacks, snowfall was less than average, and from April to June that year, only 0.2 in. of rain was recorded. In 1904, W. F. Fox wrote in “Forest Fires of 1903,” a bulletin of the NYS Forest, Fish, and Game Commission: The line of the New York Central from Fulton Chain to Mountain View was bordered with smoke and flames, except on the eight-mile stretch through the private preserve of Dr. William Seward Webb, where a large number of patrols were employed at his expense to follow each train, night or day, and extinguish the locomotive sparks that fell along the road. Many Adirondack fires were caused by live coals that escaped from unscreened locomotive stacks and fell on dry, vertical slash in the heavily logged forests along railroad lines, though Professor Emeritus of Paul Smith’s College, Dr. Michael Kudish, estimates that only about eleven percent of fires were caused by trains. More commonly, forest fires were caused by escaped campfires and brush-clearing fires, and the furnaces associated with mining operations in the Park. With the exception of mining furnaces, campfires and burning brush piles remain the top threat for wildfire in the Adirondacks today. One of the largest acreages burned during the 1903 fire season was around Lake Placid in a fire started by high winds fueling a burning brush pile. That fire spread into the High Peaks and is the one that burned down Henry Van Hoevenburg’s Adirondack Lodge. Mt. Baker in Saranac Lake burned in 1903 and again in 1908 when dry conditions and logging slash once again proliferated throughout the region. The 1908 fire spread east to McKenzie Mountain and threatened the village of Saranac Lake, as well, but it ultimately remained contained to the wilderness. In 1914, the Saranac Lake Fish and Game Club ordered 15,000 Scots pine (also called Scotch pine) grown at the State Nursery at Saranac Inn, at a price of just $60 for the whole load, and the trees were planted by a volunteer force of local men and Saranac Lake High School boys.

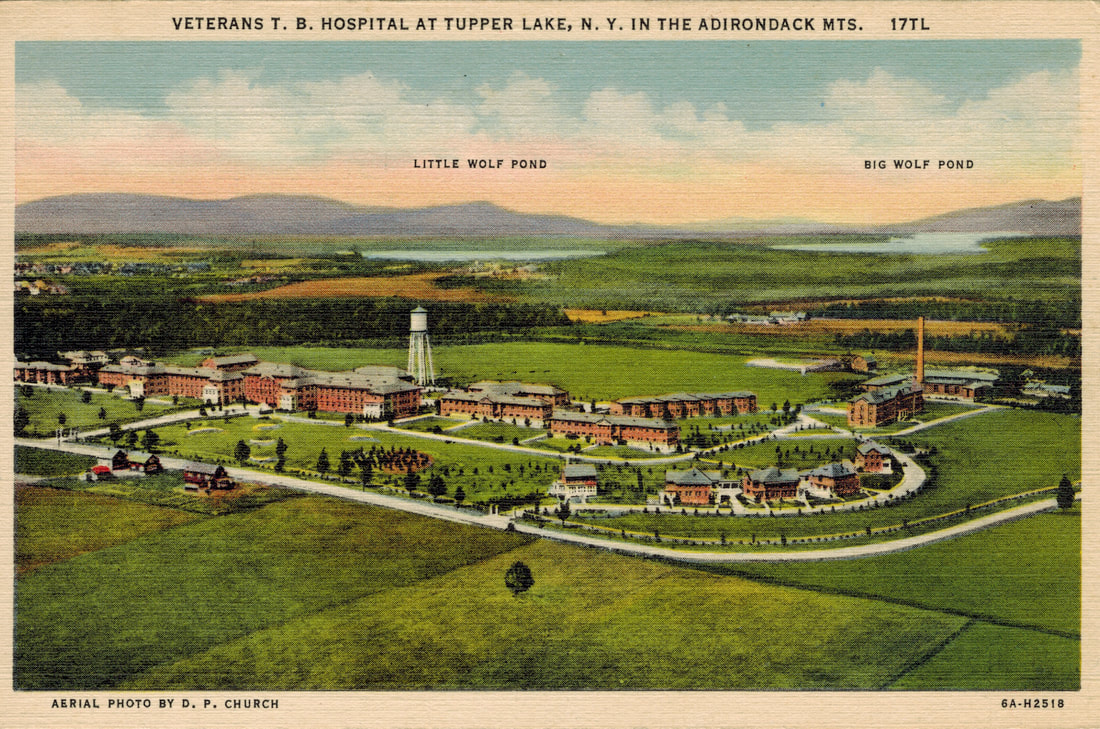

A May 15, 1914 article in the Lake Placid News states, “It is not expected that the 15,000 trees will make much of an impression on the stony sides and summit of Baker...” The prediction was wrong! Those Scots pines are still very visible as a dark green patch in all seasons up on Baker Mountain today. After fires burned over 400,000 acres in the Forest Preserve in 1903, and nearly 300,000 acres in 1908, strict laws were enacted that set up a patrol of railroad properties, forced railroads to use petroleum for steam locomotive fuel instead of coal or wood, punished those responsible for escaped fires, enabled the building of fire towers (the first fire tower built in the Adirondacks was on Mt. Morris in Tupper Lake in 1909), and gave executive power to the Governor to close the Forest Preserve to recreationists in times of high fire risk. The widespread Adirondack fires in the early part of the twentieth century were an anomaly due to the convergence of several factors including climate and fuel loads. Fire in northeastern forests has been historically absent, as shown by fossil pollen and charcoal records which estimate a fire return frequency of many hundreds to thousands of years, due to swift leaf litter decomposition, low wind risk, widely and rapidly varying topography, and the fire-resistant nature of northern hardwoods. This doesn’t mean, however, that fires can’t happen here today. We must remain vigilant and follow local regulations about campfires, burning brush, proper disposal of cigarette butts, and so forth. The first time I ever visited Vermontville it was to research the site of the 1991 fire near Kate Mountain Park that burned 300 acres. I was a graduate teaching assistant for an ecology course at Cornell University and, of all the places we could have visited in the state, we went to Vermontville because it was such an excellent opportunity to observe post-fire vegetation recovery. Now I live in Saranac Lake and coach our homeschool soccer team at Kate Mountain Park each fall, so I am watching the forest there grow a little taller each year and seeing the plants in the understory get a little more shaded out. But like we are seeing out west, slight changes in climate, exacerbated by careless actions of humans, can have drastic damaging ripple effects that will be felt for decades. Images: -Ampersand Mountain fire tower, c. 1960. Photograph by Donald Gunn Ross, courtesy of Julie Ross. -Mount Baker, undated. Library of Congress photo. In honor of Veterans Day, we're going to be sharing Tuberculosis Thursday posts about veterans all month long. The first is one of our most frequently-asked-about places, Sunmount Veterans Administration Hospital! This facility, located on the edge of Tupper Lake, opened in 1924. The VA created the hospital to treat veterans following the huge surge of TB cases among veterans of World War I. It was in operation as a VA hospital until 1965.

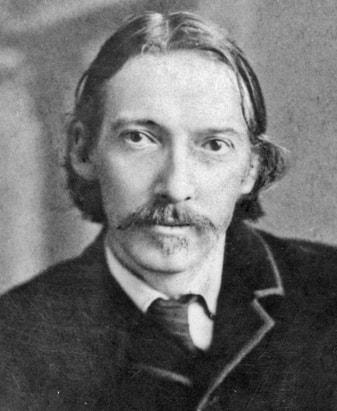

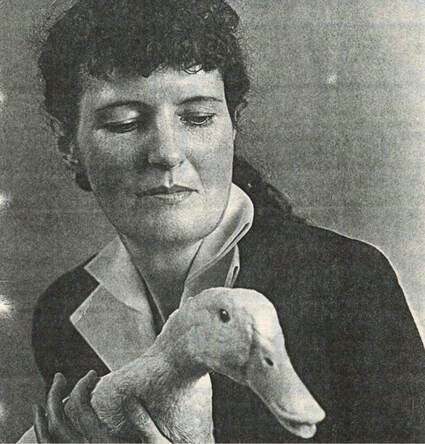

Prior to the opening of the hospital, the VA had contracts to house tubercular veterans at various private cure cottages in Saranac Lake. To learn more about the history of this facility, visit our wiki.  Robert Louis Stevenson, c. 1887. Public domain. Robert Louis Stevenson, c. 1887. Public domain. By Galen Halasz Having lived in Saranac Lake my whole life, I must say that it is a cultivating environment for all pursuits. My views may be skewed by a heartfelt bias, but with such a history of doctors, Olympians, artists, actors, and writers being nurtured in this village, I can’t help feeling that one could be anything here. I have wanted to be a writer for the past four years and so will visit the stories of notable authors who have stayed here in the past - most of them for the tuberculosis treatment we provided - and how their lives were influenced by this wonderful place, and, who, in return, made Saranac Lake even better. Everyone has heard of Robert Louis Stevenson, creator of Treasure Island and Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis and recovered at Baker Cottage for the winter of 1887-1888. I run past Baker Cottage on my way around Moody Pond, and I have to assume that Stevenson was inspired by the gorgeous view he had and also by the community of authors that had grown here. One of his greatest connections was between himself and Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, the founder of the town, a pioneer in fighting tuberculosis, and himself an author who wrote an autobiography full of his adventures here. They sometimes had fights due to firmly held opinions, but in the end, they both had a common respect for one another’s achievements and an affinity for their natural surroundings. Community and nature allowed them to continue their work even as their disease ever weakened their lungs. Another writer who sought the care of Dr. Trudeau, and another influenced by the wilderness, judging by his detailed Naturalistic writing, was Stephen Crane, author of Red Badge of Courage. Though he died at a sanatorium in Germany, his legacy remains connected to this village.  Martha Reben and Mr. Dooley. Historic Saranac Lake Collection. Martha Reben and Mr. Dooley. Historic Saranac Lake Collection. To continue the theme of writers who were connected to the wilderness, Martha Reben, with her books The Way of the Wilderness and The Healing Woods, loved the people and forests of the area when she was taking the cure. She went on adventures with local guide Fred Rice in these great woods that gave rise to her humorous and philosophical accounts. Let me apologize for not mentioning Mark Twain until now, but yeah, he was here, and he rubbed shoulders with Fred Rice too. Twain stayed on Lower Saranac Lake and was interested in the guide boats that went up and down the waterway, which surely reminded him of his hometown, Hannibal, Missouri, the inspiration for The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. He discussed the design of these boats endlessly with Fred Rice, who was a guide boat craftsman. Isabel Smith came here for the cure, but the beauty and nature that inspired her was largely unattainable, as she was more ill than the others I have mentioned. In spite of her sickness, she was compelled to write about scenery and kinship, and her book I Wish I Might makes anyone healthy who reads it cherish their freedom to be active and explore the world. This little microcosm community works its way into the hearts of every resident and visitor and was and is the inspiration for more writers than I have talked about, and I can affirm that, to this day, the literary community flourishes in Saranac Lake. I see it in the Adirondack Center for Writing’s Poem Village, in the journalism of the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, and in the novels present-day Adirondack authors churn out almost too often to follow. I see our future writing community in the participants of the Young Playwright’s Festival that Pendragon Theater holds annually. And whenever I so much as look out my village window, the inspiration I feel is electric. I see the forest, and I also feel the legacies of the writers who came before me everywhere I go; I feel how they must have felt. Touring Pine Ridge Cemetery, racing through the woods at Paul Smith’s, walking into our Ice Palace, I imagine them, the authors of the past, imagine their first breath of our fresh air, and what their adventures and friendships and mishaps must have been like in the magnificent Adirondack wild. |

About us

Stay up to date on all the news and happenings from Historic Saranac Lake at the Saranac Laboratory Museum! Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

Historic Saranac Lake at the Saranac Laboratory Museum

89 Church Street, Suite 2, Saranac Lake, New York 12983

(518) 891-4606 - [email protected]

89 Church Street, Suite 2, Saranac Lake, New York 12983

(518) 891-4606 - [email protected]

Historic Saranac Lake is funded in part by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature,

and an Essex County Arts Council Cultural Assistance Program Grant supported by the Essex County Board of Supervisors.

and an Essex County Arts Council Cultural Assistance Program Grant supported by the Essex County Board of Supervisors.

© 2023 Historic Saranac Lake. All Rights Reserved. Historic photographs from Historic Saranac Lake Collection, unless otherwise noted. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed