2 Comments

March is Women's History Month, so we're going to share images that tell the stories of women in local history. This image shows the 1931 graduating class of the D. Ogden Mills Training School for Nurses at Trudeau Sanatorium. This training school was originally established in 1913 with support from Mrs. Whitelaw Reid, and had an unusual requirement for admission--an arrested case of tuberculosis. Dr. Trudeau believed that young women who had endured tuberculosis and regained their health would have a greater understanding of patients' needs and care.

[1931 graduating class, D. Ogden Mills Training School for Nurses. Historic Saranac Lake Collection, TCR 582. Courtesy of Jan Dudones.] On Thursday, February 11 at 6PM, Historic Saranac Lake staff will present a special Zoom presentation celebrating the history of Winter Carnival. Executive Director Amy Catania will give an overview of how Carnival has evolved since Saranac Lake's first carnival in 1897. Museum Administrator, Chessie Monks-Kelly will share photos from Historic Saranac Lake's collections. We welcome community members to share their stories and photographs following the presentation! Registration in advance is required; use this form to register. Participants will receive a Zoom link via email the day before the presentation!

Image: Ice Palace, c. 1920s. Historic Saranac Lake Collection, TCR 273. Courtesy of Audrey Vanderhoof.

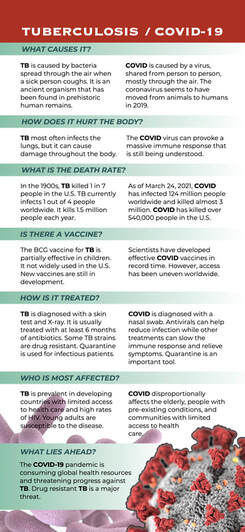

Amy Catania Dear Friends, During this quiet summer, one of the things we are missing is the theater. From Broadway in New York City to Pendragon in Saranac Lake, stages have gone dark. Actors are a lively, irrepressible bunch, and so it’s a testament to the seriousness of the situation that theaters are closed. In interesting contrast, through the 1918 flu pandemic, Broadway did not shut down. A New York Times article this past July titled, “’Gotham Refuses to Get Scared’: In 1918, Theaters Stayed Open” described how, at the height of the flu epidemic, New York’s health commissioner declined to close performance spaces. Instead, he instituted public health measures such as staggering show times, eliminating standing room tickets, and mandating that anyone with a cough or sneeze be removed from theaters immediately. The article described parallels to the current pandemic, and we Saranac Lakers would notice another connection. The lead photo from the 1918 Ziegfeld Follies included actors Will Rogers and Eddie Cantor. Eddie Cantor was one of the famous visitors to Saranac Lake. Although we have no record of Will Rogers ever coming here, his memory lives on in a beautiful local sanatorium named for him. Eddie Cantor and Will Rogers were guided in their acting careers by one of Saranac Lake’s most famous TB patients and residents, William Morris. He founded the talent agency in 1898 that still carries his name. Morris came to Saranac Lake for his health in 1902, and by the 1920s, he was spending much of his time at his Camp Intermission on Lake Colby. He was one of many theater people, from ticket takers to vaudeville stars, who make up a vibrant part of Saranac Lake history. While the show went on, TB was a common hazard of the job, and the theater community did not ignore the need for support. Empathy is an essential part of the job description for an actor, so it’s no surprise that many people in the entertainment business engage in helping others. Impresario and theater owner Edward F. Albee led efforts to provide subsidized care to workers in vaudeville at three different cure cottages in the village. William Morris and his wife Emma established the Saranac Lake Day Nursery to provide childcare and nutrition to children in need. Morris brought to Saranac Lake some of the most famous entertainers of the time to raise funds for many causes. Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, and Harry Lauder performed for fundraisers to support the Day Nursery, the Jewish Community Center, the Methodist Church, and St. Bernard’s Church. Morris brought actress Olga Petrova to Saranac Lake to turn the first shovel of earth for a housing project on Lake Street. William Morris helped found the National Vaudeville Artists Home in Saranac Lake in 1929. In 1936, following the tragic death of Will Rogers in a plane crash, the facility took the name Will Rogers Memorial Hospital. It was a fitting tribute to the great American humorist, actor and vaudevillian, known throughout America as the country’s “Ambassador of Good Will.” In service today as a beautifully restored retirement community, the building hosts a stage where TB patients once put on performances. The Will Rogers Motion Pictures Pioneers Foundation in Los Angeles continues to support workers from the entertainment industry in need. During the TB years, Saranac Lake children visited Will Rogers Hospital for holiday concerts. There, they serenaded the patients in the stairwell that wound up around the Will Rogers statue. Today, the tradition continues, when school children sing to elderly residents for the annual winter concert. For now the stage and stairwell are quiet, but actors are irrepressible. We can trust that someday soon, the show will go on again. **** The Last Letter from the Porch What started as weekly letters written from my porch during quarantine would now, 23 letters later, be more appropriately named “Letters from the Busy Museum.” There is much work to be done as we move forward with a major project to expand the museum, and it’s time to bring this series to an end. As they say, the show must go on! Going forward, Historic Saranac Lake will continue to share a weekly column with our members and the Adirondack Daily Enterprise. We welcome your help with this effort. Please get in touch to share what you know about the amazing history and architecture of the Saranac Lake region! Thank you for helping to make history matter, and be well, Amy Catania Executive Director Historic Saranac Lake Images:

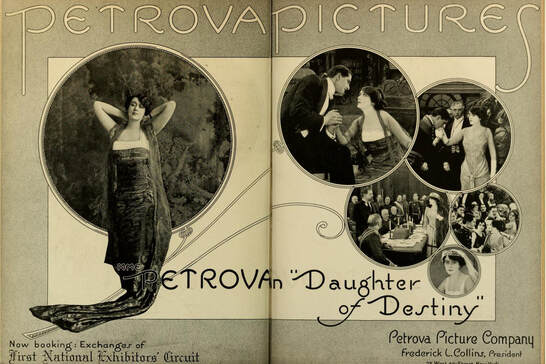

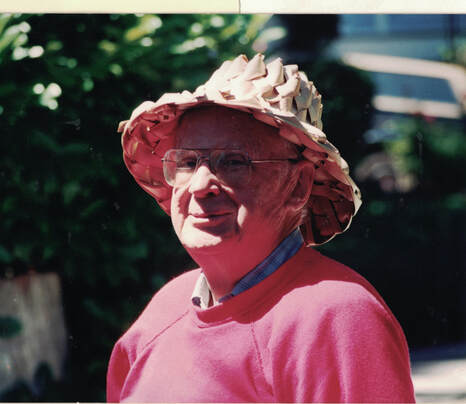

-Advertisement in Moving Picture World, Nov. 1917. Public domain image. -Dr. Edgar Mayer, actor Eddie Cantor, possibly Al Jolson, and theatrical agent William Morris. Courtesy of Gail Brill. -Saranac Lake High School chorus students pose with banner of Will Rogers in the stairwell at Saranac Lake Village at Will Rogers following last year’s winter concert. Courtesy of Historic Saranac Lake. by Amy Catania In a time when compassion and logic often seem in short supply, many of us have a newfound appreciation for doctors and scientists. Saranac Lake’s history is full of professionals in medicine and science who had a passion for learning and an intense curiosity about the natural world. Our own Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau was a naturalist at heart. He learned an interest in the natural world from his father James, who accompanied his friend John J. Audubon on scientific expeditions. When Edward fell sick with TB, he credited the peace he found in the Adirondack forest for his ability to fight the disease. Later, that same appreciation for nature inspired Trudeau to pursue the scientific study of tuberculosis. In 1882, Dr. Robert Koch announced his discovery of the tuberculosis bacterium. Trudeau learned of his study and rushed to replicate Koch’s work, despite never having used a microscope himself. Motivated by his desire to find a cure and his own curiosity, Trudeau demonstrated incredible persistence in the face of adversity. He began his work in a remote, freezing village with no running water, electricity, or train service. As he stated in his autobiography, “One of my great problems was to keep my guinea-pigs alive in winter.” Trudeau worked with improvised laboratory equipment, and even when his first home and home laboratory burned down, he didn’t give up. Trudeau died of TB in 1915. An effective antibiotic treatment would not be perfected for almost forty years. In the meantime, Saranac Lake’s community life would be enriched by the intellectual curiosity of countless men and women in medicine and science. One such person was Dr. Lawrason Brown. Believing it important that patients taking the rest cure keep their minds occupied, Brown encouraged them to study various crafts, ornithology, and botany. In 1905, Dr. Brown established the open-air workshop at the Trudeau Sanatorium to provide formal training in occupational therapy. Dr. Leroy Upson Gardner served as the director of the Saranac Laboratory from 1927-1946. He performed the first study to show a connection between cancer and asbestos, and he led efforts to understand other industrial diseases such as silicosis. Dr. Gardner’s passion for science extended to botany. Alice Wareham recalled participating in a wildflower contest for the children who attended the Baldwin School. The teacher was surprised when Alice found what she thought was a yellow trillium, and didn't believe her. Alice asked Dr. Gardner, and instead of saying, "you're wrong", he said, "show it to me." She did, and he confirmed that it was a rare mutation of a yellow trillium. Over the years at Historic Saranac Lake, we have had the pleasure of meeting many relations of Dr. Gardner. Our understanding of local history is enriched by personal relationships we have developed with descendants of Drs. Ayvazian, Baldwin, Blanchet, Bristol, Brown, Decker, Gardner, Heise, James, Keet, Leetch, Long, Meade, Merkel, Neely, Packard, Pecora, Sandhaus, Schwartzberg, Seidenstein, Shefrin, Steenken, Wolinsky, and of course, Trudeau. We all have a story of a doctor who has made a difference in our lives. My grandfather, Dr. Landon Bachman, served as a beloved pediatrician in Millbrae, California, for some fifty years. After retirement, he continued to read his medical and scientific journals, and he turned to gardening. Instead of caring for children, he nurtured flowers every day until the fog rolled in. A tangled maze of color, my grandfather’s garden was a beautiful representation of his life’s work of caring for life itself. Today, we are grateful for doctors and scientists like Trudeau, Brown, Gardner, and Bachman who continue to improve the world with their curiosity and compassion. Images:

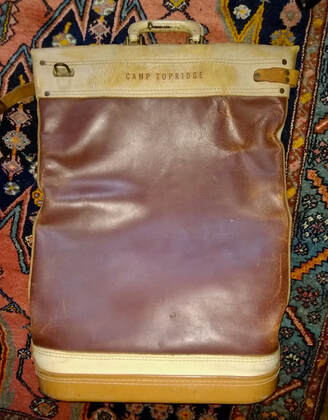

-Doctors in Saranac Lake, courtesy of Jan Dudones. Pictured left to right: John N. Hayes; unknown; Homer Sampson; Dr. Warriner Woodruff; Dr. Spencer Schwartz; Dr. E. R. Baldwin, with hat; unknown; Dr. Fred H. Heise; Dr. Francis Berger Trudeau; unknown; Dr. John H. Steidl. -Dr. Leroy Gardner, courtesy of Tom Downs. -Dr. Landon Bachman in gardening hat, courtesy of Amy Catania. by Amy Catania In times of trouble, some of the most essential workers are the people who deliver the mail. It can get lonely here in the Adirondacks, where there are more trees than people. Mail carriers keep us connected, and post offices in rural hamlets serve as social hubs. Post offices, like schools, were less centralized back in the day. Mom and Pop operations were the norm. George Henry Carley, Sr. served as the first mail carrier in Lake Clear starting in 1912. He made his deliveries by sled in winter and horse and buggy in the summertime. Until a few years ago, mail boats delivered to the docks of camps on Upper Saranac Lake. Many historic camps had their own leather mail bags. The Corey’s post office delivered mail to the camps of Upper Saranac Lake by the steamer Saranac. Several large institutions had their own post offices, such as the Ampersand Hotel and the Trudeau Sanatorium. The owner or head of the institution served as the nominal postmaster. Hotel employees or TB patients sorted and distributed the mail. Eventually, mail service was all centralized in the village at a post office called "Saranac Lake, New York." Looking for some good stories, I called up retired mailman, Tom Clark. For some 35 years, Tom’s smile brightened the village as he speed-walked his daily route. Tom liked his downtown walking route, because he got to visit with shopkeepers and their regular customers. He also delivered to the houses along Riverside Drive. By moving fast in some parts of the route, he made the time to slow down and visit with his favorite longtime customers. Some of his older customers waited for him with cookies and lemonade. Their talks with Tom were often their main social contact of the day. Mailmen stepped in and helped out with sudden emergencies. Tom remembers one day when a customer rushed out to him in a panic, with a bat loose in her house. Tom got rid of the bat for her and continued along his way. Tom kept a stash of biscuits in his pocket and made friends with the neighborhood dogs. Occasionally, he had to deliver the cremains of a deceased pet, sent from the veterinarian by certified mail. That was always a sad day for the owner and for Tom. Tom joined the postal service because he recognized it as a good, steady job that would allow him to raise his family in his hometown. As a kid, he remembers seeing a mailman at Mark's Bar having a beer after work in his uniform. Tom thought to himself, “that seems like a cool job.” When he started delivering mail in the 1970s, Tom joined a crew of longtime clerks and carriers. The “old guard” were a tight-knit group who knew everyone in town. Locals remember George Booth, John Campion, Don Meachom, Nick Mitchell, Bob Nelson, Bob Oddy, Del Oldfield, Joe Quigley, Cal Reed, Charlie Sayles, Inky Schenck, Roddy Stearns, and Dick Toohey. Almost all served in WWII, or Korea, or both. They came home from war to serve in the post office. After work, they drank beer together at Journey’s End and the Elk’s Club. They put money in the pot all year to save for a big holiday party. As Tom neared the end of his career, the post office began changing in ways that made it a less rewarding job. Management no longer consists of locals who had made their way up in the ranks. There is a growing focus on automation and efficiency. Most deliveries are now made by mail truck rather than on foot. Mail carriers are monitored by GPS, and they have to meet exact times and quotas. What’s the worth of a first class postage stamp? As the postal service reconfigured its business model, the personal relationships Tom made with his customers and colleagues were never part of the calculation. As email, text messages, and social media replace personal letters, the post office has a different place of importance in American life. Mail carriers no longer deliver as many personal messages, but they do bring census forms, ballots, stimulus checks, medicine, and essential items. Today, mail carriers move fast all day. There’s no time for long visits over lemonade. But they know who we are, and they deserve our appreciation. Images:

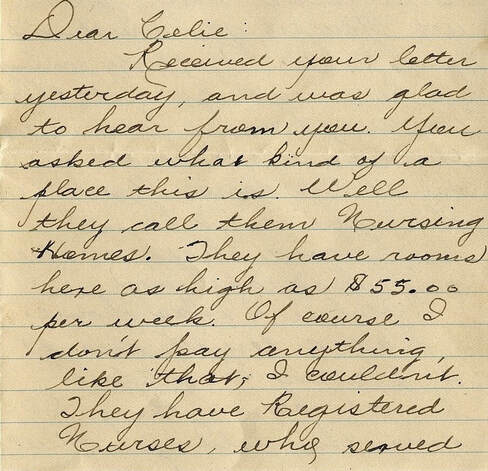

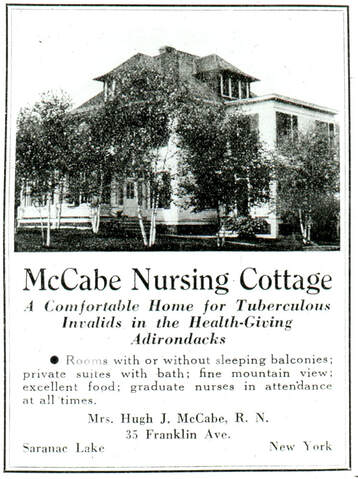

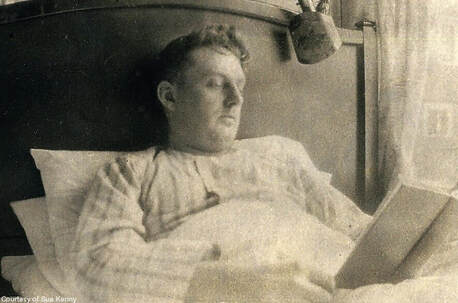

-George H. Carley, Sr. in mail wagon, Lake Clear Junction, c.1915. Courtesy of Historic Saranac Lake -Camp Topridge Mail Bag, Private Collection. -The Trudeau Post Office, Courtesy of Florence Wright. -Joseph Quigley and George Booth were WWII Veterans and part of the “old guard” at the post office. Courtesy of Adirondack Daily Enterprise. by Amy Catania The fresh air cure wasn’t all a bed of roses. First-hand accounts left behind in letters, photographs, diaries, and memoirs paint a picture of life in Saranac Lake during the TB years. It’s an incomplete record that can lead us to believe curing was an overwhelmingly positive experience. It takes energy, time, and a degree of mental and physical well being to leave behind a personal record. People who were very ill, illiterate, or struggling with poverty did not have the same opportunity to create, or later preserve, accounts of their experiences. Thousands of people whose names we do not know suffered and died in Saranac Lake without leaving much of a trace. Coffins were put on the train under cover of night. History, as they say, belongs to the victors. Today, more historians are thinking about which stories get preserved and told, and why. We are more aware of our bias to pay attention to stories told by people who look like we do. With this in mind, in recent months we have been working to document this historic time by welcoming community members from all walks of life to tell their stories. Over the course of several months, our Oral History Coordinator Kayt Gochenaur has set up a table in town to interview passers-by, asking for their help documenting the time of COVID. Saranac Lakers report discovering new talents and strengths during this time, just as many TB patients did during their cure. Some people report newfound creativity, resilience, and spiritual growth. But we have collected many sad stories too — stories of financial troubles, health worries, struggles with addiction, and loneliness. Both sides of the story often surface in the same person. Both sides belong in the historical record. Sometimes we come across a sorrowful story from the past, and it stands as a reminder of many that have gone unrecorded. John Patrick (Jack) Kenney was a young husband and father from Brooklyn who became sick with tuberculosis when he was 26 years old. Jack was one of eight siblings born to Irish immigrant parents. TB wiped out half of his family, killing his father, two sisters, and his brother. Jack came to Saranac Lake in July 1930. He stayed at McCabe Cottage on Franklin Avenue and fought desperately to get well, but he died within the year. During his cure, Jack wrote letters home. His granddaughter saved eight of his letters and provided copies for our wiki website. Jack’s letters are full of financial worries and anxiety about the welfare of his wife and small children back in Brooklyn. Jack wrote to his wife with detailed instructions about how to visit without spending too much money. “If the riverside is closed tell the cab driver you want to go to the Hotel Alpine. Both of these places receive early visitors from that train. When you get there, do not hire a room, but ask for the dining room. Then go in and order breakfast. Then ask the waitress where the ladies room is and wash.… The reason why I don’t want you to hire a room in the hotel is because they are rather expensive… Wear your best clothes as they are rather stylish up here. Also take with you a change of clothes & dress warm.” Jack shared about his fight with TB, writing, ”This damn disease is very discouraging. One day you feel good and the next terrible. It is very hard to realize that they are making any progress at all. Your progress, if any, is extremely slow.” In the last letter he wrote, “My throat is awful sore, sometimes I think I am never going to get better. I am making a novena and Ella and the girls are too. That seems the only salvation. These doctors cannot create miracles. They can only help you. The throat doctor is a bit heartless. When he cauterizes my throat it sure does hurt. Sometimes I think it will never get better. Well, I will leave it in God’s hands.” Jack died two months after writing that last letter. In a strange way, his letters provide some comfort now. Here, ninety years later, we walk the same streets that Jack’s wife travelled when she visited her sick husband. Like her, we wonder about our health, our future, and how to stretch a dollar. We are not alone. Images:

-Letter from John Patrick Kenney to his wife, August 1, 1930. Courtesy of Sue Kenney. -Kayt Gochenaur collecting stories for Historic Saranac Lake’s “Saranac Lake in the Time of Covid” project. -Advertisement for McCabe Cottage from the Journal of Outdoor Life, Historic Saranac Lake collection. -John Patrick Kenney curing in Saranac Lake. Courtesy of Sue Kenney. by Amy Catania As autumn approaches, schools are thinking about ways to keep students safe by maximizing time outdoors. The concept of outside instruction is not new. Leading up to WWII, open air schools were built in the United States and Europe to protect children from tuberculosis. Even in Saranac Lake, where temperatures in the winter tend to stay well below freezing, some children attended unheated, open air classrooms. In the mid-1920s, the Saranac Lake School District built an open air school at River Street, at a cost of $12,000. All Saranac Lake children were weighed periodically and X-rayed annually. Those found to be underweight attended the Fresh Air School. The building, now used for a nursery school, is located behind the former River Street School. In 1937, the Fresh Air School moved to a new six-room addition built at Petrova School. Open air education wasn’t just for preventing illness and improving health. It was also widely used in summer camps as a natural extension of the camping experience. At local camps over generations, children have learned skills outdoors, such as arts, crafts, sports, and music. The Deerwood Adirondack Music Center was a large summer music camp near Saranac Inn that operated from 1943 to 1957. The camp accommodated 50 students between seven and twelve years of age, and 100 older students. Deerwood’s music director Sherwood Kains brought in a distinguished faculty and guest artists. The great Hungarian composer, Béla Bartók, who came to Saranac Lake for his health in the early 1940s, served on the faculty at Deerwood in 1944. Every Deerwood camper sang in the choir. Weekly concerts were held at the Harrietstown Town Hall in Saranac Lake and at the Sunmount Veterans Hospital in Tupper Lake. Béla Bartók attended one of the concerts at the Town Hall, where students performed a piece that he had written. Former campers have written to us over the years, sharing stories and photos from their time at Deerwood. Camp programs in our museum archives document a place where young musicians worked hard and had fun too. While the camp attracted talented young musicians from far-flung places, we do not see people of color in any of the photos. Jewish campers did attend Deerwood, representing a departure from the long history of exclusion of Jewish people from the Northern part of Upper Saranac Lake. Music ceased to ring out across the lake in 1957, when Kains died and the camp closed. The property sold at auction, and most of the buildings were demolished. But Deerwood lives on in the memories of many campers. In 2012, Molly Sykora McCrory wrote to us of her experience as a camper in 1944 and 1945: "Each precious experience has continued to shape my life: singing the Messiah and other master works (as a 12 & 13 year old!!); exhilarating Friday night concerts in town; sitting at lunch when the announcement was made that WWII was over (complete silence, tears - all campers were stunned and turned immediately to their music for comfort); the entire camp walking to the train station to bid good-bye to expelled campers (for smoking) -all singing "The Lord Bless You and Keep You"as the train pulled away (gorgeous!); practicing piano under the trees (music ringing all day throughout the woods)…. I am almost 80 now, but I wish my grandchildren could have had such an enriching summer.” Traditionally, summers in the Adirondacks come alive with music, but this season is oddly quiet. We miss concerts by the Lake Placid Sinfonietta and Loon Lake Live. We miss the voices of Gregg Smith Singers, Northern Lights Choir, and Adirondack Singers. We miss enchanting evenings with friends at Cobble Spring Farm. But music waits in our future. Just listen as you drive by the high school, and you might hear the sweet sound of a student taking a music lesson, outside. Images:

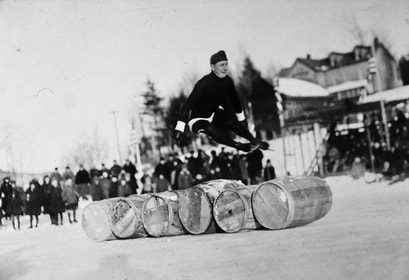

- Saranac Lake Fresh Air School. Courtesy of the Saranac Lake Free Library. - Bassists at Deerwood, Historic Saranac Lake collection. - Saranac Lake High School band teacher Keith Kogut teaching a fresh air trumpet lesson this spring. Courtesy of Josh Dann Dear Friends, A winning sports team, like a beautiful ice palace, grows out of a strong community. It’s no surprise that Saranac Lake has a long tradition of athletic achievements. From team sports like bobsledding, baseball, hockey, football, and curling to individual competitions like speed skating and barrel jumping, Saranac Lake history is full of athletic men and women who left their mark. Today, Covid-19 is disrupting so many traditions, and sporting events are some of the hardest to give up. The cancellation of competitions is heartbreaking for athletes, and it’s hard for the spectators too. In small towns like Saranac Lake, sport brings generations together to enjoy a brief moment when all that matters is the kids on the field or the ice. No matter how fast or slow, each child shines for a moment. Over time, parents come to know each others’ children, and we cheer for their victories too. It might be easy to see the cancellation of sports as a first world problem. But athletic competition is more than entertainment. It goes back in early human history as a fundamental expression of human culture. From the ball game played by the ancient Maya, to soccer around the world today, sports are a strong social glue across time and place. This is not the first time global events have swept away the joy of sport. During WWII, athletics went on hold around the world. The Olympics of 1940 and 1944 were cancelled. During the war, there was no Tour de France, no Wimbledon, no U. S. Open, no international speed skating. Instead, young women took to wartime work, and young men went off to war. In 1943, Saranac Lake’s champion bobsledding team, the Red Devils, left their sleds behind for the war effort. Bobsledders who served in WWII included names like Morgan, Latour, Bickford, Fortune, Keough, and Duprey. These men’s athletic careers were interrupted, but their legacy lives on. Just look at rosters of Saranac Lake teams today, and you’ll see many of those same last names. Sports, like history, connect us to community and provide a broader perspective. No matter what you accomplish, there’s almost always someone better and faster. Most victories and losses will fade with time. It takes a lot of work and more than one stroke of luck to foster a team that history will remember. In the last few years, a group of standout coaches has steadily built a dynasty of cross country running in Saranac Lake. In the last two years, the boys team won the State Class C title. Now seniors, they were poised to win at state’s again. This time they had a strong chance to come out on top of all classes — all New York schools, big and small, public and private. The Saranac Lake team had their sights on the national race in Oregon. It was a once in a century, if ever, opportunity for a small community. The pandemic has taken it away. It’s not the first disappointment for the cross country team. Two years ago, they qualified for the NY State Federation meet, something that only one other Saranac Lake team had done before. But a freak snowstorm cancelled the race, and suddenly the season was over. It was a huge disappointment, but what did the boys do? They laced up their sneakers and went out for a run in the snowstorm. Saranac Lakers honked their horns to cheer them on. A shopkeeper bought them hot chocolate. The team ran down to the new Aldi and bought themselves a bag of candy. It turned out to be a pretty good day. The cancellation of this year’s championships is a big blow, but it’s no surprise that the team is taking it in stride. They know sports are about far more than winning. When asked how he’s feeling about it, one runner said that the team is sad for the coaches. The kids wanted to win for them. In our hearts, the boys will make it to Oregon. Best of all, we’ll be seeing them around town, running fast in the snow together. Be well, Amy Catania Executive Director, Historic Saranac Lake (and one of the proud parents of the SLHS cross country team) Images:

- The Saranac Lake Red Devils Bobsledding Team. Historic Saranac Lake collection, courtesy of Natalie Leduc. - World champion speed skater and barrel jumper, Ed Lamy. Historic Saranac Lake collection, courtesy of Dick Jarvis. - Natalie Bombard (left) pictured with Ed Lamy’s daughter, Ruthie. Natalie grew up to win the New York Women's Slalom Championship in 1948.. Historic Saranac Lake collection, courtesy of Natalie Leduc. - The Saranac Lake Cross Country team running in the snowstorm on the day of the cancelled Federation Race, 2018. Adirondack Daily Enterprise photo. |

About us

Stay up to date on all the news and happenings from Historic Saranac Lake at the Saranac Laboratory Museum! Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

Historic Saranac Lake at the Saranac Laboratory Museum

89 Church Street, Suite 2, Saranac Lake, New York 12983

(518) 891-4606 - [email protected]

89 Church Street, Suite 2, Saranac Lake, New York 12983

(518) 891-4606 - [email protected]

Historic Saranac Lake is funded in part by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature,

and an Essex County Arts Council Cultural Assistance Program Grant supported by the Essex County Board of Supervisors.

and an Essex County Arts Council Cultural Assistance Program Grant supported by the Essex County Board of Supervisors.

© 2023 Historic Saranac Lake. All Rights Reserved. Historic photographs from Historic Saranac Lake Collection, unless otherwise noted. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed